- Home

- Sophie Ward

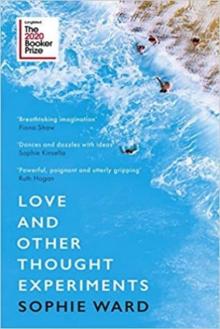

Love and Other Thought Experiments

Love and Other Thought Experiments Read online

Sophie Ward is an actor and writer.

Her book, A Marriage Proposal; The importance of equal marriage and what it means

for us all, was published by Guardian short books in 2014

She has a degree in Philosophy and Literature and her

PhD at Goldsmiths focused on the use of narrative in philosophy of mind.

Copyright

Published by Corsair

ISBN: 978-1-4721-5458-3

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Sophie Ward

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Corsair

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

For Rena

The Imagination is not a State: it is the Human Existence itself.

William Blake, Milton: A Poem in Two Books

I’ve dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas; they’ve gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the colour of my mind.

Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights

If we are going to make further progress in Artificial Intelligence we are going to have to give up our awe of living things.

Daniel Dennett, Speaking Minds: Interviews with Twenty Eminent Cognitive Scientists

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

1. An Ant

2. Game Changer

3. Sunbed

4. Ameising

5. Clementinum

6. The Goldilocks Zone

7. Arthulysses

8. New to Myself

9. Zeus

10. Love

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Rachel picked up the magazine that Eliza had left in the kitchen. The cover was a drawing of a tree with the roots embedded in a man’s head and above him a blowsy crown of leafed branches arched towards the sun. It wasn’t a typical image for Eliza’s reading matter. Rachel turned the page.

‘Thought experiments are devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things.’

That’s a lot, thought Rachel. But she liked the sound of it. It tickled her to think of stories being used by scientists. I could be a thought experiment, something Eliza has dreamed up to challenge her hardened reasoning.

‘If I were a thought experiment,’ Rachel asked Eliza as they got into bed that night, ‘What one would I be?’

‘I’m not sure you can be a thought experiment,’ Eliza said. ‘They are supposed to help you think about a problem.’

‘If you can imagine it, then it is possible.’

‘That is one theory.’

‘So,’ Rachel pushed away the book Eliza had picked up and blinked at her girlfriend. ‘Imagine me.’

Eliza smiled and shook her head. ‘This is what happens when the fanciful encounter the factual.’

‘I’m not sure which is which here. Quit stalling.’ Rachel prodded Eliza’s armpit.

‘Fine! You want to be a thought experiment? You can be a zombie! No, no, I’ve got it. You would be, yes, Hume’s Missing Shade of Blue. The colour he has never seen but can still visualise. Happy?’

Hume’s Missing Shade of Blue, thought Rachel as she laid her head on the pillow. Yes. I can be that. ‘Tell me some more.’

1

An Ant

Pascal’s Wager

The seventeenth-century mathematician Blaise Pascal argued that since God either does or does not exist and we must all make a decision about the existence of God, we are all bound to take part in the wager. You can commit your life to God because you stand to gain infinite happiness (in the infinite hereafter) with what amounts to a finite stake (your mortal life). If you do not commit your life to God you may be staking your finite life for infinite unhappiness in Hell. By this logic, the infinite amount of possible gain far outweighs the finite loss.

But there is here an infinity of an infinitely happy life to gain, a chance of gain against a finite number of chances of loss, and what you stake is finite.

Blaise Pascal Pensées 272

‘The ants have moved in here now.’ Rachel brushed the small body aside and turned the pillow over.

Eliza glanced up from her book.

‘The ants. In the sitting room. They’ve followed us in here,’ Rachel said.

‘Are you sure?’

‘I just saw one.’

‘No, are you sure it’s an ant? They’re so tiny, I don’t know how you could tell.’ Eliza returned to the hardback that was balanced on her bosom.

‘I don’t need glasses.’

‘Yet.’

Rachel prodded her. ‘Do ants bite?’

‘I’ve got to finish this for tomorrow.’

‘It’s definitely ants. The same ones that were on the sofa last summer. They got in through the gap in the window and now they’ve found a way in here. You couldn’t put a baby in a room with ants. Eliza?’

‘Yes?’

‘Did you see them before? When you slept on this side?’

‘No.’

‘You wouldn’t have noticed anyway.’

‘Maybe one.’

‘Is that why we swapped sides?’

The book fell away from Eliza’s hand. ‘What?’

‘Nothing.’

‘No. Tell me. You think I moved you to that side of the bed because it’s infested?’

‘It’s okay. Read.’ Rachel looked at her girlfriend. ‘I know. Sorry.’

Eliza didn’t go back to her reading but she kept the light on while Rachel fell asleep. She wondered whether she should get the pest controller from down the road to look at the flat. Mr Kargin. He had a second job repairing and selling old televisions. They had walked into his workshop one day, to buy an aerial for Rachel’s black-and-white set. The man spent a long time looking through cardboard boxes and muttering about outdated equipment.

Eliza saw Rachel trying not to mind the posters on the wall, each one with a picture of a cockroach or a rat, along with a method of extermination. There were so many different creatures and all the pictures were the same size so the termites were as big as the squirrels. Mr Kargin stared at them both for some time.

‘He stared at me,’ Rachel said when they walked away from the shop. ‘He was fine with you.’

He didn’t find an aerial and he was bad tempered about the entire transaction though it had been his idea to start rummaging through the boxes. Eliza didn’t imagine he made much money in television repairs but she thought the extermination business might be a means of expression as much as an extra income. She had promised Rachel they would never go back.

Rachel lay next to her, breathing heavily. It had been Eliza’s idea to change places because she had a new desk and it wouldn’t fit in the alcove on her side of the bed. It was a practical decision and even Rachel could see that it made sense. The flat was already crowded with furniture and the desk could double as a bedside table, but maybe the desk had disturbed a nest or maybe it was the time of year for ants to move

indoors. Eliza had not deliberately changed sides because of the insects but now she would have to prove that she cared enough to fix the problem. Ever since they had talked about having a baby, Rachel had been testing the temperature of Eliza’s love.

Eliza wondered how many of her decisions were basically points of honour. Throughout her life, her job at the university, the bicycles and vegetarianism, even her haircut seemed as if they were chosen in reaction to the opinions of an invisible audience. She had become the sort of person she approved of but she wasn’t sure she had chosen anything she actually wanted. She checked the pillow one last time and turned off the bedside light. She would sort out the ants in the morning.

program

The next day, Eliza cycled past the television repair shop on the way to work. Smaller versions of the vermin posters were stuck inside the display window below precarious stacks of broken televisions. She thought of all the chemicals that the bad-tempered Mr Kargin would use in their flat. He seemed to radiate poison. Even ants didn’t deserve a murderer like that.

They had talked about the ants over breakfast and Eliza had googled ‘getting rid of ants’.

‘All these ants look regular-sized. I can’t find any photos of extra small ants.’

Rachel didn’t want to read about eggs and nests.

‘I don’t mind one ant. But not in our bed, and not hundreds of them. I keep thinking of that song … “just what makes that little old ant …”’

‘Peppermint oil.’ Eliza twisted round from the screen to watch Rachel singing while she stacked the dishwasher. ‘It says here they don’t like peppermint oil. Well, that’s easy. I’ll get some later.’ She closed the page and went back to her emails.

‘I like the idea of the peppermint oil but I can’t see how it will stop the ants in the long term …’ Rachel wiped down the kitchen surfaces and went to stand by Eliza’s chair. She rested a damp hand on Eliza’s shoulder. ‘They’re very tiny but even if they got the oil on their feet or paws or whatever ants have at the end of their legs, it’s not going to hurt them.’

‘They don’t like the smell.’

‘So much for “High Hopes”.’

Helloworld;

Eliza arrived home with a small vial of peppermint oil from the chemist.

‘It seemed awful to get it from the supermarket, like we wanted to feed them.’

Rachel picked up the vial and left the bag from the chemist on the table.

‘I got you something else.’ Eliza nodded at the bag.

Rachel continued to examine the label on the peppermint oil as though it might list something other than oil of peppermint. After a moment, Eliza turned back to the kitchen counter and poured herself a glass of white wine. She hadn’t intended to buy an ovulation kit on her way home from work, but while in the chemist she had looked around for a present to cheer Rachel up. This is how life’s decisions get made, she thought, you choose a fertility test instead of bubble bath. She looked at the paper bag on the table. The pink box had been pulled out and Rachel was leaning back in her chair with an air of expectation that Eliza felt she couldn’t meet.

‘Thank you.’

Eliza frowned. ‘It’s a start.’

‘Yes.’

They were too tired to wash the skirting board with peppermint oil. Rachel got into bed and glanced down at the floor. She caught Eliza’s eye when she looked up.

‘Nothing.’ Rachel smiled.

Eliza diagnosed it as a non-duchenne smile, a pet subject of hers. It didn’t reach her eyes. Still, Eliza knew she was trying.

Rachel pulled at her pillow. ‘It’s when I’m going to sleep. I think of them crawling about.’

‘That’s a normal reaction. Like when we think about nits and our scalps feel itchy.’

‘Nits?’ Rachel coughed. ‘Who has nits any more?’

‘Kids have nits. If we had a child we’d get nits.’ Eliza touched Rachel’s hand which was already rubbing the back of her head. ‘You haven’t got nits now!’

‘But we have got ants, Els. I’m not imagining them.’

Eliza brought Rachel’s hand to her lips. ‘I know, my darling.’ She kissed each of Rachel’s plump fingers just below the nail and grazed the tip of the thumb with her teeth.

‘Babies aren’t all bad.’

‘Hmmm?’ Eliza paused.

‘Nothing. Don’t stop. It’s nothing.’ Rachel curved her hand round her girlfriend’s cheek and lay back into the pillows. ‘Don’t stop.’

Eliza leant over her. ‘I bought the test, remember? I read the book. Now, close your eyes and let me kiss you ’til you fall asleep.’

uses crt;

Eliza sat up in a panic. She was in bed, in the dark. Beside her, Rachel pulled at the pillows.

‘Rachel? What is it? What’s the matter?’

‘Something bit me. In my dream, we were in a field and the sun was shining and there was grass. You said, “Stay still” and I tried but …’ Rachel lifted her pillow. ‘It bit me.’

Eliza struggled to reach for the bedside light. Rachel’s cries had disturbed her own dream. ‘The grass bit you?’

‘In my eye.’

Both women squinted in the dim lamplight.

‘Show me.’

Rachel’s breath caught. ‘It was you. You stabbed me with the grass.’

Eliza felt the sweat cool on her skin as she pushed back the bedclothes.

‘Rachel, you were asleep.’

‘An ant.’ Rachel ran to the full-length mirror that hung behind the door.

‘You had a nightmare.’

‘It’s gone in my eye.’

Eliza sat in the bed and yawned. ‘Come here and let me have a look.’

Rachel perched on the bed and lifted her face to Eliza. Deep by the innermost corner of her eye was a livid red mark.

‘You’ve scratched yourself. Poor baby.’ Eliza put her arms around her shivering girlfriend.

Rachel couldn’t stay still. ‘I don’t think so.’

She walked around the bed and pulled back the bedclothes. They both stared at the damp and wrinkled sheets. There were no ants.

‘Nothing there,’ Eliza said. ‘Do you want some antiseptic? Rachel?’

Rachel had dropped to her hands and knees on the floor. The pine boards were old with a thin layer of varnish. It had taken Eliza and Rachel three days with a rented sander to get them smooth enough to walk on but the wood was still uneven and pitted and some of the gaps were big enough to lose an aspirin through. As Rachel knew well enough.

‘It’s the middle of the night. I’ve got to be at the lab at eight. Please, Rach. Let’s look in the morning.’

‘I won’t sleep.’ Rachel sat on the cold boards and looked up at Eliza. Her wavy hair had formed tight curls at the temples and tears dripped from the scarlet eye.

‘Oh, honey. Hey. Hey there.’ Eliza slid over to Rachel and crouched down on the floor beside her. ‘Ohhh. It’s okay.’

Rachel bent forward and sobbed into the crook of Eliza’s neck. ‘It’s not. It’s not okay. My eye hurts and an ant has gone into my head and you think … you think I can’t look after a baby.’

Eliza pushed her girlfriend far enough away to see her face. ‘Where did that come from?’

‘You know it’s true. Every time we talk about it you say you want to go through with it and that Hal is cool. Your egg, my womb, his sperm, like a recipe or a poem. But nothing ever happens and then we’ll be doing something else and you’ll be completely different, really negative, like it would be awful to have a baby. Like tonight …’ Rachel rushed into the question on Eliza’s lips. ‘Tonight, when you started talking about the nits.’

‘Oh, for god’s sake. Children get nits, that’s not an excuse, it’s just what children do.’

‘But it’s not why you said it. You said it because you thought I couldn’t handle anything; that I don’t know about the real world, about real life. And maybe I don’t.’ Rachel sat and sobbed. Her shoulders heaved and

her breath came in shuddering gasps.

Eliza watched her for a minute. She saw the sad and frightened woman in front of her from a distance, as though she was not on the floor with Rachel in their comfortable flat at three o’clock in the morning but looking in through the window on her way to somewhere else in her busy, busy life. In their four years together she had often felt like this, both there and not there, connected, yet keeping a part of herself separate, as though for emergencies. And Rachel had let what Eliza offered be enough. That was the problem with a baby. Not Rachel, who was a bit scatty and did lose things and wasn’t exactly a career woman. None of those things mattered. She loved Rachel, but the baby would use up Eliza’s emergency rations.

‘I don’t.’

Rachel let her breath go. ‘You don’t what?’

‘I don’t think you’ll be a bad mother.’

‘Really?’

Eliza shook her head. ‘You’ll be great at it. Wonderful. I’m the one to worry about.’

Rachel laughed and wiped at the wetness that had pooled around her nose and mouth. ‘You! You can do anything. You’d rule the world if you wanted to. With those legs.’

They both looked at Eliza’s long legs as she folded them beneath her and sat back on her heels. Rachel’s legs were short and the skin was soft. On other nights, Eliza liked to trace messages on Rachel’s thighs. Nonverbal Communication, she wrote. And, Sensory Pleasure.

They held hands as they knelt in front of each other.

‘We look like we’re getting married, in some ancient ceremony,’ Rachel said, her voice raw from crying.

‘Yes.’

‘We’re going to, aren’t we? We’re going to get married and have a baby. Doesn’t have to be in that order.’ Every crease on her face shone in the lamplight.

‘Yes, my darling.’

They tilted towards each other and rested their foreheads together.

‘Now, this is how you get nits.’ Eliza bumped her head against Rachel’s.

‘Not like this?’ Rachel pushed herself into Eliza, knocking her off balance and landing on top of her.

‘Hey!’

Love and Other Thought Experiments

Love and Other Thought Experiments